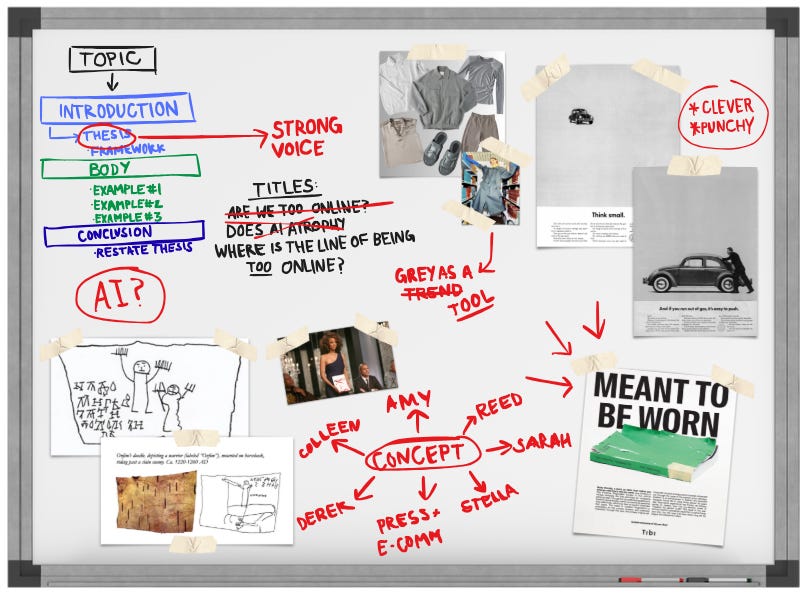

Where is the Line of Being Too Online?

Will the AI wave atrophy our ability to tell stories the good old-fashioned way?

I write a lot of copy.

In fact, a sizeable chunk of my day-to-day life is spent writing copy. Long-form, short form, social media captions, you name it. To most people in my field, writing copy is likely viewed as a monotonous task—I’ll admit that some days, when the words just aren’t flowing, it can certainly feel that way. Outside of work, my social ch…